Here’s a question primarily asked to Bible Teachers (Preachers); but, by all means, others’ comments are welcome.

I was asked recently, ‘Don’t you think all sermons should essentially have one main thing to walk away with?’

(Don’t be a pedant like me and rush to correct the dangling preposition! Few understand the correction and even fewer appreciate the correction)

Almost immediately, I answered ‘yes’; but, in my characteristically annoying fashion, added, ‘Well, yes, more or less, er, but with some qualifications…why do you ask?’

When I started off over 30 years ago in what I consider the best but most humbling job — Bible teaching– I was trained according to a model forwarded by Perry Miller. Miller claimed the preacher is an expositor (so I wasn’t misled into thinking a sermon is to be a devotional chat, systematic theology lecturer, mystical message or Garrison Keillor-wannabe ramble). Let the text, in its context, drive and shape the sermon. Summarise your message in one ‘thesis statement’. Whatever subordinate points you employ they should ONLY exist to further your thesis statement. By they way, Miller strongly insisted that application should never wait to the end of the sermon but run throughout the entire sermon.

Many years later, when I returned to teach at a US Anglican theological college (US = seminary) students were using the expression ‘Big Idea’ which comes from the excellent work by Haddon Robinson. As I listened to the method in practice (and one of the finest, clearest Anglican preachers in the States I knew at the time was Peter C Moore), it seemed eminently correct.

But here’s my question: on what grounds do we accept this assumption? Stay with me here, please.

First, is this assumption largely a matter of rhetoric? Is it largely a late-modernist device (Yikes! I hate using this cliche because some people love to blame everything on the Enlightenment and celebrate everything postmodern). But for the sake of conversation, how much should the genre of the text suggest the rhetoric or homiletic?

Second, while a thesis statement/big idea is clearly helpful, do ALL Biblical genre lend themselves to this method? For example, does narrative, poetry, apocalyptic or parable? I want to be clear (although most people who hear me would privately tell you I am not) I think clarity is vital. But is it possible that in my laudable desire for clarity I end up delivering a kind of reductionism — reducing the text to simple propositions which, in turn, could become either moralisms or trite cliche?

Third, what do people mean by the expression ‘one thing’? Is it a thing to do? A thing not to do? A thing to think? A thing to feel? If the original question is a poorly phrased request for more application, fair enough. On the other hand, and I don’t wish to be controversial here, could it be that sometimes, some people, want me to do their thinking/reading/reflecting and tell them ‘here is this week’s one thing’? They don’t want irony, complexity, or, er, hard work.

So, what do others of you think? Let me know…

This past Saturday (3 April 2010) a friend of mine, Mark Ashton, vicar of St Andrew’s the Great Church, Cambridge, went at last to be with his Lord and Saviour, the Lord Jesus Christ. I appreciate this sounds too much like a cliche but it is the rock solid basis of Christian hope. For those of you who also knew Mark, and knew him far, far better than I, you will know that Mark was no cliche and his confidence in the full gospel of Christ was no commitment to a superficial cliche.

I first met Mark around 25 years ago. Tremendously insightful, strongly opinionated, not a little intimidating but consistently encouraging and caring to me (and others). Several years later, we worked together at a preaching conference in the States and I remember how careful, gracious and patient he was with American Episcopalians (not known for either an interest or skill in expository preaching). He was inspiring and encouraging to the Americans.

Throughout the years I had occasional contact with Mark, including a visit he made to the theological college in the States where I taught and was vice-principal. Some of my colleagues there also knew Mark and highly valued his ministry.

It was in 2005, when we finally returned to the UK after our time in the States, when I saw best Mark’s huge gifts. We met in Cambridge for a Chinese meal lunch. I had some personal issues and questions to discuss with Mark. Once again, he was patient, caring and insightful. He didn’t need to meet with me; he had far more important things to do; but he did so nonetheless. Both then and now I am thankful.

But intriguingly Mark has done one last thing for me (and, assuredly, for thousands of people who knew him at StAG). His death in Christ on Holy Saturday speaks huge volumes of the hope and promise given to all who trust and believe in Jesus. Mark’s death is a “life well lived”. He died well in that he pointed all of us to Christ.

Yesterday, my wife, Janet, was in a conversation with a young employee of a major department store here in London. Initially, it was about makeup, skin care and colouring. As the conversation furthered, however, they commented on one another’s non-British accent. After 25 years in the UK, Janet’s accent suggests somewhere in the middle of the Atlantic Ocean. The young woman whom Janet met that day spoke flawless English but came from another European country.

As they chatted the woman mentioned to Janet that she finds living in London very hard. In particular she finds life in England lonely. Janet asked her what she meant by this. She went on to say that she finds London people cold and unfriendly, rude even. The young woman immediately pointed out that Janet is one exception but then qualified her comment by saying, “But, of course, you aren’t British!”

What took Janet aback, however, was when the woman went on to express her sadness concerning her experiences of racism in London. Apparently, she reported, because of her skin colouring and her accent she believes Londoners treat her dismissively and, she said, with occasional disdain. She ended up saying to Janet, “I wish I could meet nice, friendly English people!”

Janet said she’d be delighted to introduce her to folk we know who are wonderfully friendly and welcoming. Truth is, we are privileged to meet and know lots of very kind and friendly English people. But, as she later told me, the one part of the conversation that troubled her was the comment about perceived racism. How is this countered?

One film especially deconstructed my self-belief that I am free from all racist problems — Paul Haggis’ Crash (2005). Some time ago I posted some thoughts about this film.

If you’ve seen the film you’ll recall how artfully this film reveals the sub-level propensity towards racism in just about all of us. On one hand, therefore, what the young woman said to Janet about her experiences in London (whether she is correct or not, I don’t know; but it is her perception nonetheless) ought not to surprise us. Racism has not been eradicated despite efforts to promote multi-culturalism and greater tolerance.

On the other hand, countering racism (in whatever form) cannot be accomplished by legislation, exhortation or compulsion. Civil liberties and legal accountability are necessary and in this limited scope legislation is vital. But telling someone to do something or be something isn’t ever ultimately successful. “Laws” or “rules” cannot change the human heart, redirect the human will and promote human society. There is, frankly, something about us that is profoundly out of sync that can only be corrected, healed and transformed by something or someone greater and more authentic than legal or rule imposition.

This means that while I’d like to hope that Londoners can make a difference by civility, politeness and courtesy (all of which are virtues), I suspect all of this could result in self-efforts (however good they be initially) that simply go only so far. Truth is, a more radical and more profound change is necessary in me and others here in London (and, of course, elsewhere).

Once again, I am struck and intrigued by what the Jew, Paul, who was an apostle of the Lord Jesus Christ, wrote to his fellow Christians who were non-Jews but sharers with Paul in a new humanity/new society brought about in Christ:

10 and have put on the new self, which is being renewed in knowledge in the image of its Creator.

11 Here there is no Greek or Jew, circumcised or uncircumcised, barbarian, Scythian, slave or free, but Christ is all, and is in all.

12 Therefore, as God’s chosen people, holy and dearly loved, clothe yourselves with compassion, kindness, humility, gentleness and patience.

13 Bear with each other and forgive whatever grievances you may have against one another. Forgive as the Lord forgave you.

14 And over all these virtues put on love, which binds them all together in perfect unity. (Colossians 3:10-14)

This past Saturday, Janet and I went to see the current exhibition at Tate Britain (Millbank in London) entitled, Turner and the Masters. See Tate Britain

JMW Turner (1775-1851) is one of Britain’s most important and influential artists — after whom the prestigious Turner Prize is named. He is sometimes identified as a Romantic painter but I also see that he is also called an Impressionist and Landscape artist. I’m left with the conclusion that Turner is hard to pigeon-hole.

What I did not appreciate is his biography. Turner was the son of barber and wig maker, from whom he probably received his strong work ethic. While there is no suggestion of any class anxiety on Turner’s part it is, nevertheless, not impossible to imagine that much of Turner’s competitiveness and inner sense of being driven to exceed arose out of his own upbringing. Thankfully, however, the curators at the Tate did not indulge in any of this kind of psychoanalysis. They offered us something far better and more interesting.

The Tate exhibition deftly shows the relationship between Turner and some of the Grand Masters of Europe (such notables as Rembrandt, Van De Velde , Poussin and, especially, Claude Lorrain. Turner looked back to these European greats and “emulated” some of their techniques and touches. Turner’s use of light, some of his themes and some of his subjects are directly borrowed from these earlier artists. Emulation was an important statement of respect and appreciation.

Yet Turner also was willing to attempt things on a grander scale: he emulated or borrowed from the past out of an aspiration to show not only his indebtedness to the past but his equality with the past and, even, his superiority to the past. This is a particular feature of the exhibition at the Tate: it shows us the complex nature of Turner’s respect for the past and his own drive to show his equality with the past. Evidently, Turner was driven by the need to show his patrons and wider “audiences” that he too could be classified as a “Great”. Turner went even so far as to “compete” with his contemporaries (Constable) and those younger than he to show his own prominence.

Turner unquestionably was a hugely gifted artist — there’s little doubt of this. Nevertheless, as the Tate exhibition reveals, he did not always succeed in substantiating his equality with some of the Great Masters. Turner, in some cases, simply couldn’t “come up with the goods”. Personally, when I compared Rembrandt’s use of light and his painting of windmills to the imitations of Turner, my vote went to Rembrandt. This isn’t to take anything away from Turner!

Here is a link to a video about Turner and the exhibition from one of the Tate’s curators:

If you have the opportunity to see this exhibition, by all means do so! It is worth the admission price and the Tate Britain should be commended for this level of exhibition.

One thing I did notice and it made me ponder for some time: I didn’t see that many young people (under the age of 30) at the exhibition. Of course, one Saturday’s attendance does not an irrefutable fact make — the place may have been heaving with young people on other days. Still, I did wonder if young artists are encouraged to view the Grand Masters and their heirs. Is emulation an important feature in today’s training? Or is novelty and the iconoclastic more highly prized?

I don’t mean to pose a facile question here. I simply wonder if some of the ways we educate and train people today ends up falling short because: (a) We think the past has nothing really worth considering (b) We indulge young people in believing they already “have artistic gifts within them waiting to be released” and so rush them on to this moment of “actualisation” or (c) We, ourselves, have lost contact with the past.

An Australian friend (and this guy knows what needs to be known!) passed on to me some links to some of the better coffee shops (I have to find a better term than this) here in London.

London isn’t immediately known for its coffee houses — although, historically, it once was and should be now!

Check out these recommendations and spread the word if you find a place you like!

See \”Top 10 coffee shops in London\”

See also \”Taylor Street Baristas\”

This month’s recommendation is the latest CD from female artist, Yvonne Lyon. Her Ashes & Gold (Emu Bands under license 2009) is available through iTunes. You can visit Lyon’s web site, Yvonne Lyon Music for more information about her and earlier CDs. Three particular commendable qualities:

First, this CD has superb production quality. Full credit goes to both Lyon and her husband, David, but also to the folk at Foundry Music Lab. The sound quality is rich, tightly arranged and creatively mixed. It’s a pleasure listening to excellent recording production! This quality enlivens the good backing musicians — notably some outstanding string accompaniment.

Second, Lyon’s musicality is refreshing and simultaneously captivating. It’s sort of hard to classify her music: it is a mix of acoustic, folk and ballad. To my ears (and this is entirely subjective!) she vocally echoes some of Shawn Colvin and Sarah McLachlan. Lyon’s acoustic guitar work is very good but her piano is even better (both, again enhanced by the excellent production quality).

Third, her lyrics are intellectually rich and poetically suggestive. Personally, I enjoy good musicality with thought-provoking lyrics. In this CD Lyon gave me both, and in spades! The opening track, “Feel the Light”, expresses some of her experience when she visited Cambodia. So, too, are the haunting and provocative words of “The Reckoning” — also arising out of her visit to Cambodia.

Other songs convey the paradox of beauty and brokenness,

All is not perfect/All is not torn/All is not wasted/The bruised and the worn/We’re walking through ashes and gold/And all is not lost (“All Is Not Lost”)

My sense is that Lyon sings not of simplistic optimism but of what is substantial — a substance ‘touched’ and ‘realised’ because, as she puts it, “We are not alone”. But, I don’t want to give the game away. I suspect she might dismiss my suggestion that she herself is someone who,

She sees all the colours that we used to see/But don’t look for these days

She hears a world that doesn’t speak of doubt or fear/And she’s amazed at all the the tiny things/All the tiny things (“Tiny Things”)

Check out this latest CD from Yvonne Lyon and listen carefully. You’ll be rewarded.

Thomas Friedman offers his opinion on what President Obama should say when he soon accepts his Nobel Peace Prize. Personally, I think Friedman is spot on here; I would only add that the President should add British troops to the list!

I was shocked, embarrassed and then chilled to read of the story of someone or some group placing a poll on Facebook concerning President Obama and asking people to vote whether he should be assassinated. Perhaps it was all some big joke? The humour is lost on me!

I was shocked, because it could easily be a contravention of a Federal law; embarrassed because living here in the UK I’m asked by British friends why such and such takes place in the American political scene (but how in the world would I ever know?!); and chilled to think of the poisonous rhetoric coming out of quarters in the US. I’ve lost count of how many friends on Facebook now refer to Obama as ‘socialist’ or ‘out to destroy our country’ and ‘leading an administration that hates the military’ or ‘trying to brain wash US school children’. What is happening?

Whatever happened to sane public discourse? Of course one can disagree and disagree strongly with elected politicians, including the President! Disagreement and debate (even heated debate) are cherished privileges enshrined in the founding documents of the US. But the present vitriol and diatribes coming out is disproportionate.

Thomas Friedman, writing in the New York Times (which, OK, many of my US friends will write off as part of the liberal media monster) clearly states the nightmare scenario seemingly developing before us.

As the saying goes, “Is it art imitating life or life imitating art?” A good friend in the States (thanks, Joel!) alerted me to this New York Times article by Garry Wills (professor of history emeritus at Northwestern University outside of Chicago) entitled, “Entangled Giant”. See Garry Wills, \”Entangled Giant\” NY Times

Wills’ thesis is this: since the end of the Second World War the intelligence community (C.I.A. and National Security Agency and others) has grown in size, power and influence. Coordinate with this has been the shift of balance towards the executive branch (the Presidency and the White House staff — think West Wing) and the global fears — first, of Communism and “the bomb” and, most recently, Islamic terrorism. There arose both a need for the intelligence community and the community created a need for its’ existence.

The result is, according to Wills, that no administration of either party is able to extricate itself from the tangled webs of the arcane and hugely inter-associated world of the “Spooks”. Neither party can legitimately claim any moral high ground, on which to stand and make change; and neither party is free from the pragmatics and temptations associated with the use of intelligence resources. In short, Bush and Cheney aren’t the only questionable characters because Obama (so far) isn’t doing all that much different.

All of which might imply: (a) that no one administration or party is really able to govern without getting “dirty hands” and (b) that the story lines of characters like Jason Bourne and Jack Bauer are not at all that far-fetched. Simply put: art may well imitate life but life may also imitate art…and who can tell the difference anymore? But since things today (think of Iran’s missile testing and alleged developments of nuclear weaponry) are far, far more serious and dangerous than an episode of 24 or Spooks (even though both of these are some of my favourite programmes to watch) would portray, the role of our intelligence agencies and the governing authority of our elected leaders is morally and politically profound.

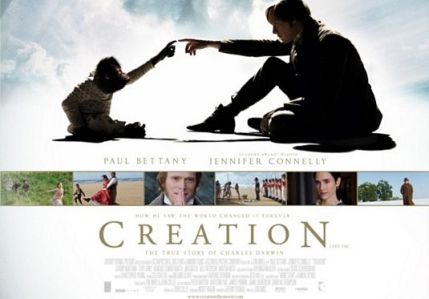

This past Friday saw the UK release of the much-anticipated film, Creation — staring Paul Bettany and Jennifer Connelly (who are, in “real life” husband and wife). See Official movie web site The film is directed by Jon Amiel, who directed both The Man Who Knew Too Little (1997), the satirical comedy with Bill Murray, and the TV mini-series The Singing Detective (1986).

Creation is going to raise the temperature in the never ending battle between “creationists” and “evolutionists” (appreciating that these two terms are infuriatingly difficult to define with precision). The film covers the period just before 1858 when The Origin of Species was published. The film poignantly reveals the love between Charles Darwin (Bettany) and Darwin’s wife, Emma (Connelly) — a love that attempted to carry the huge burden of their differences. Darwin was not an atheist but rather, according to his own expressions, agnostic. Emma, on the other hand, was a devout and thoughtful Christian. You can already sense one theme within the film.

Let me warmly encourage folk to take advantage of the excellent work produced by the folk at Damaris — a UK work that helps people engage with contemporary culture (notably but not exclusively film). They’ve come up with good resources for individuals, churches and small groups to watch the film, respond to the film and undertake good, sane and productive conversations. See Culturewatch from Damaris

In this posting I’ve linked to a good article by Tony Watkins, whose reflections on this film (and others) is very helpful.

In as much as there is a big business surrounding the “evolution v creation” battle, along with the consummate culture wars involved, this film will contribute in a big way. Ideally, it would be good if the film contributed to better dialogue and conversation amongst us. I’m enough of a realist (or do I really mean cynic?) to think it will probably end up hardening people on either side of the line. This will be a shame. But check out the Damaris resources, see the film and get a group of people together to talk about it!